In late 2024, Urban Strategies hosted a Collaborative Dialogue at our Vancouver studio, bringing together an intimate group of city-builders to share ideas and perspectives on the housing crisis in BC.

The format was an informal roundtable discussion that followed Chatham House Rule (comments not to be attributed to a speaker). Discussion questions were provided to spark ideas and conversation.

Part of our mandate at Urban Strategies is to convene dialogues – to collaborate with others across sectors and probe some of the pressing topics affecting our day-to-day lives. Few topics are more persistent than the ongoing housing crisis. It currently dominates discussions in politics, media and across the real estate industry, not just in British Columbia. While the conversation focused on the crisis in BC, we know it extends across Canada and beyond to many other parts of the world.

The housing crisis is generally characterized by a shortage of affordable housing and high housing prices.

The crisis is attributed to a variety of factors, which can make it challenging to identify solutions. Often-cited causes include:

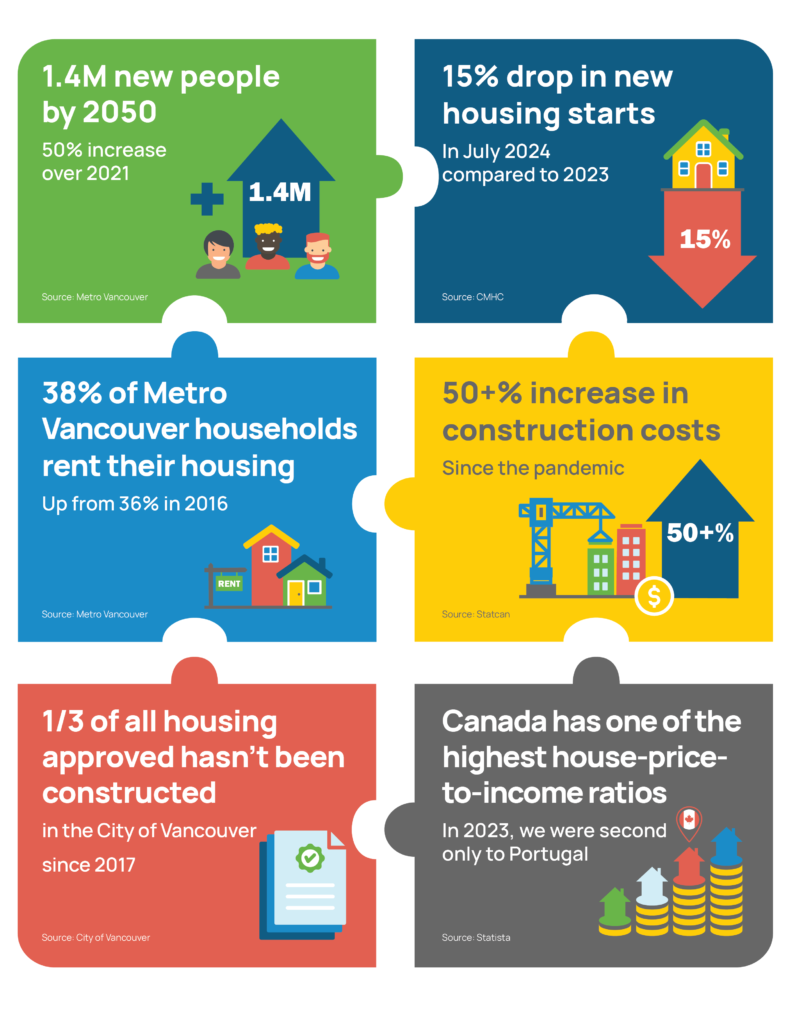

The high cost of building is prohibiting new housing starts. This includes high interest rates, which are slowly declining, but have been considered an influential factor in limiting housing starts. Similarly, high labour and construction costs are constraining housing starts. These costs have increased exponentially since the pandemic. Canada’s house price-to-income ratio, which is among the highest in the world, means that house prices are growing faster than incomes, making housing increasingly unattainable for potential buyers. Population growth is another factor driving the crisis;Metro Vancouver’s population is expected to grow by 50,000 people per year, reaching 4.2 million by 2050. This is a nearly 50% increase from the 2021 population of 2.8 million. International migration is expected to be the main driver of this growth. Another commonly cited cause is policy failures, such as the government’s exit from the construction and operation of affordable housing that happened in the 1990s.

We’ve seen different levels of government responding in different ways to this crisis. At a provincial level, we’ve seen governments pulling different leavers to unlock housing supply, including the legislation introduced here in BC this past fall, which has required significant action from local governments. At a federal level, funding programs, such as the Housing Accelerator fund, have been introduced to support efforts to address the crisis. While there is a lot of attention on the topic, it’s not clear how all the activity to address it is going to move the needle.

Defining the housing crisis and its causes

A wide range of issues and concerns were raised as the discussion kicked off around what the housing crisis is and what is causing it, indicative of how complex and multi-pronged the problem is. The key matters raised include:

The crisis is both a supply and demand problem.

As population projections show, a significant influx of residents is anticipated in Metro Vancouver in the coming years. People will continue to come to BC not just from other countries, but other parts of Canada. BC is the retirement resort of Canada, and it has been “discovered” by Canadians. In addition to the demand from population growth, land has become an investment vehicle as its value continues to rise, especially in places like Vancouver. Investors see land as a stable, long-term asset, with opportunities ranging from residential and commercial development to agricultural and recreational uses. According to Statistics Canada, about half of condos in Vancouver are investor owned, purchased via presale and rented out as secondary rental properties to avoid empty homes taxes. (This isn’t necessarily a Vancouver-specific problem, of course: Toronto rates are comparable.)

Despite the current and anticipated demand, we are seeing a decline in housing starts year over year due to a number of factors, including high costs and a weak presale market.

The City of Surrey demonstrates how there are ways to accommodate population growth without significant new housing starts. As the fastest growing municipality in the region, one that will soon overtake the City of Vancouver in total population, Surrey is growing rapidly while adding very few correlating new units. One way this influx of newcomers is being accommodated is through secondary suites; 51% residents live in such units, in many cases providing more affordable accommodation, while helping to make home ownership more attainable for landlords. It also begs the question of whether the type of housing being supplied meets the needs of residents. There is general agreement that the supply of family-oriented housing is insufficient to meet the needs of our communities.

Time is money, and money is risk.

The most significant factor in decision making regarding the developability of a site is the financial return across the time matrix. Lenders are very conservative about risk and entitlement is a significant risk and can meaningfully impact costs. The longer the timelines for entitlement, the greater the impact on the bottom line. As such, any measures that fast track the entitlement process reduces the impact of time on the risk calculation.

Other risk factors include the cost of building in the context of increasing labour and material costs and high interest rates. All risks are measured across the costs of time. The longer the time, the higher the bottom line.

Another risk is the ability to sell units profitably; is there a market for the units when they come online? Despite a high demand for housing, there are many people who cannot purchase homes at the price required to make them profitable for developers.

It is not a singular problem and actions to address it are having unintended consequences.

The housing crisis is a multi-faceted issue that needs to be addressed through a cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary approach. It is not unique to BC, or even Canada, and is connected to economic and social factors that extend beyond our borders.

While a lot of action is being taken at all levels of government in Canada, there is a concern that there is a game of “whack-a-mole” being played, where you introduce a policy or program to address one problem and inadvertently exacerbate or cause another one. These unintended consequences create new problems that need new solutions. From a political perspective, the issue is being simplified as policy makers search for a the right vaccine to save us from the crisis. However, it’s a much more complex problem than one with one, or even a few solutions.

An example of unintended consequences includes BC’s Provincial ban on foreign buyers; when this came into effect, investors started buying vacant sites to park their money. They are not developing these sites, but rather parking their money, which functions to dampen the supply and increase the price of land due to demand.

In addition, there are now so many incentives for rental that strata development is prohibitive. These include tax credits, direct subsidies, and funding programs. While rental supply is desperately needed, the limited construction of new strata could serve to contract the condo market and increase prices.

Actions are being taken to address the crisis

There is optimism about the future impacts of current initiatives.

A bright spot in the efforts to address the crisis is the recent partnership between the Musqueam Indian Band, Squamish Nation and Tsleil-Waututh Nations (MST) and the province. Called the Attainable Housing Initiative, it promises to deliver over five million square feet, or 7,500 units of housing with a large percentage of family units. These will be offered for purchase at 40% below market rates. If other government partners come to the table with funding, they may be able to increase this promise from the current 5 million to 10 million square feet. The province has indicated the attainable housing model will be rolled out across BC, but details have yet to be shared.

This form of shared-equity home ownership provides security of tenure and allows owners to benefit from an increase in the value of the home. It also makes room for middle-class families with children that have been shut out of the ownership market. It’s aimed at housing front line staff, such as nurses and firefighters, who are often drawn to lower housing prices in communities outside of Vancouver. In a crisis such as an earthquake or flood, these workers may not be able to get to work, exacerbating the challenges facing the city; the attainable housing strategy would offer some resiliency in a scenario like this.

Part of motivation behind the attainable housing initiative is that MST currently has 25 million square feet of entitlements on their books, which is a risk because the market can’t absorb this product. Sales need to move faster; at current absorption rates, it would take over 50 years to deliver, so there’s motivation to find ways to develop faster. This isn’t due to a lack of demand, but rather the affordability of the product.

Another positive step noted by the group is efforts by organizations, such as the Rental Protection Fund, to acquire existing rental buildings, maintain affordable rents, and assist housing operators and nonprofits to purchase land to develop additional rental. These efforts are an important part of the path to retaining affordable rental stock.

Also seen as a win has been the move by many municipalities to eliminate parking requirements for new developments. This is a key tenant of BC’s Bill 47, which eliminates parking requirements within designated transit-oriented areas. The City of Vancouver has gone a step further and eliminated minimum vehicle parking requirements for all land uses, city-wide (there remain minimum requirements for visitor parking and accessible parking). These initiatives will reduce the significant cost burden of below grade parking provision and encourage more sustainable forms of transportation.

Another initiative in the efforts to address the crisis are steps being taken to remedy the skilled labor shortage; all levels of government are paying attention and trying different approaches, including foreign credential recognition program, enhancing apprenticeship opportunities, adjusting immigration policies to attract skilled tradespeople, and more. The results of these policies will take time to have a meaningful impact, but it’s important that they start now so they can catalyze change in the coming years.

As city builders, we have a role in enabling change

There is a need to add nuance to the dialogue and influence the conversation.

As city builders, we need to remind people that this is a complex issue, and we need to avoid oversimplifying it by relying on a small number of pointed solutions. It’s important to emphasize that it’s an issue with many tentacles and we must look at the big picture and recognize the potential impact of solutions on other parts of the problem. Cities are complicated organisms, and we can’t solve things with a focused solution.

It is essential that all levels of government work in unison and not in isolation to address the problem. It’s also important that decision makers are taking a long view to solutions that recognize how entrenched this problem is. We also recognize that this cannot be addressed by city-builders alone, that there are many people with a wide range of leavers that need to be involved in solutions. So far, the solutions aren’t having the needed impact and those tackling the problem need to innovate and continue to develop new ideas and approaches to tackle the challenge.